Thomas Chatterton, whose career among all those of English men of letters was the most eccentric, was a posthumous son of a poor man who, besides being a choir-singer, kept the Pyle Street School in the city of Bristol, England. In a small tenement-house near by he was born, November 20, 1752. The mother maintained her two children, Thomas and a daughter two years older, by keeping a small school for girls. At the age of five years the boy was sent to the Pyle Street School, where the master, unable to teach him anything and deciding that he was an idiot, dismissed him. For a year and a half afterward he was so regarded. During this time he was often subjected to paroxysms of grief which were expressed generally in silent tears, but sometimes in cries continued for many hours. By many an expedient of a parent who understood him not, from frequent serious affectionate remonstrance to an occasional blow upon his face, he was led or forced along. One day this parent, while about to destroy an old manuscript in French, noticed the child looking with intense interest at the illuminated letters upon its pages. Withholding the paper from its threatened destruction she briefly succeeded in teaching him therefrom the alphabet, and in time from a black-letter Bible he learned to read. Not long afterward the family removed to a house near the Church of St. Mary Redcliffe, one of the oldest and noblest among the parochial structures in England. In a room called the Treasury House, over one of the porches of this church, was a pile of ancient documents, muniments of title, parish registers, and other things, which had been removed by the latest Chatterton, and which were kept in the house now occupied by the family. The boy when eight years old was sent to the Blue Coat, a charity school, where he learned with rapidity the elements taught thereat. The time not occupied with school tasks he devoted to reading whatever books he could borrow or obtain from a circulating library. While engaged in study he seemed unaware of everything passing around him. At twelve years of age he probably had read a larger number of books than any child who ever lived.

It is curious to study how the genius of some persons is developed and their destiny determined by the conditions of their childhood. The Chattertons for a hundred and fifty years had been sextons in St. Mary Redcliffe, the last being John, uncle of the poet. Whatever might have been in the transmission through several generations of ghostly interest in this monument of the Middle Ages, it is known that to Thomas Chatterton it was of all earthly objects the one most interesting. For the sports of other lads he had no heart; his leisure time was spent in the church, and in the study of its history and its varied quaint literature. In time he began to imitate the ancient manuscripts now in his mother's house, and with ochre, charcoal, and black lead, his success in that line was marvellous. These habits induced others kindred, among them absence of mind, under whose influence, sometimes, when in the company of others, he gazed silently at and about them with dreaminess, as if he was thinking how to connect contemporary things strange to him with those, his only familiars, two centuries before. It seems a pity for such a spirit to be without other guides than a weak, toiling mother, and a teacher dull and despotic as the head-master of the Blue Coat School. Of other things than books he had opportunities to learn little. The sense of honorable duty, either he had not been taught or its principles had been inculcated in ways too meaningless to make enduring impression upon his being. Under influences more benign he might have made a career, if not more brilliant, more felicitous. At the age of ten years he wrote some verses entitled "On the Last Epiphany," which, printed in Farley's Journal, showed that he had, if not high poetic genius, at least extraordinary sensibility of rhythm. Unfortunately his mind conceived for most of what he saw around him a hostility which drove him to express it in satirical phrase. A church-warden, whose name of Joseph Thomas would not have survived but for Chatterton's verses, was made immortal for the changes made by him while intent upon destroying ancient monuments, interfering with his own ideas of churchyard regularities. Some of the levellings of this man, particularly of an ancient cross mentioned by William of Worcester three centuries back, were scourged with a lash much imitating that of Alexander Pope, perhaps the only really existing poet whom he sought to imitate. Praises accorded to him inspired the feeling that if he could meet opportunities entirely favorable, he could become illustrious; and it is touching to note that in this ambition his leading thought was to be able to lift his mother and sister far above their lowly estate. Insufficiently taught in principles of personal rectitude, persuaded that greatest possessions were obtainable mainly through fraud, he commenced that strange career which none but a mind so little instructed could have failed to see must end in disaster. There can hardly be a doubt that insanity, if not born with him, was settling upon his understanding and that no degree of careful guidance or successful venture would have imparted entire relief.

In his fifteenth year he was apprenticed to John Lambert, an attorney of Bristol, by whom he was set to copying legal documents, an employment that lent many hours of leisure, which he devoted to study in heraldry and Old English. With these he became familiar, and then he began those impostures that were the bane of his short remnant of life. The first of these had for its victim, one Burgum, a pewterer, whose ignorance and vanity exposed him to the lad's designs to obtain money from him by flattery. Like many others in such conditions, the pewterer had eager desire to be thought a descendant of ancestry formerly of high lineage. One day he was told by Chatterton that among the ancient parchments appertaining to Saint Mary Redcliffe, he had discovered one with blazon of the De Bergham arms, and he intimated that from that noble family he, the pewterer, may have descended. The document was made out wholly by Chatterton. Investigation satisfied Burgum fully, and in return for the discovery he gave the boy a crown-piece. This compensation seemed so inadequate that the discoverer afterward celebrated it thus:

"Gods! What would Burgum give to get a name

And snatch the blundering dialect from shame?

What would he give to hand his memory down

To time's remotest boundary? A crown!"

A year afterward, on occasion of the completion of the new bridge over the river Avon, he astonished the whole town by a paper printed in the Bristol Weekly Journal, with the signature of "Dunelmus Bristoliensis," which was pretended to have been discovered among those multitudinous papers of the Treasury House, and which gave account of the city mayor's first passage over the old bridge that had been dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin by King Edward III. and his queen, Philippa. Search for the sender was expedited by his offer of further contributions on the same line, and wonderful was the success attending his devices. No less than the other citizens was misled William Barrett, a learned surgeon and antiquary then engaged upon a history of Bristol. This man, who had been signally kind to the orphan, availed himself freely of his pretended findings, paid for them liberally, and used them in the preparation of his book. What pleased him most was the discovery that Bristol, among other notables two centuries back, had a great poet in the person of Thomas Rowlie, a priest, who, among other things, had written a great poem entitled "The Bristowe Tragedie; or, the Dethe of Syr Charles Bawdin," founded upon the execution of Sir Baldwin Fulford, in 1461, by order of Edward IV. This was indeed a great poem. The muse of tragedy had inspired the young maniac with much of her consuming fervor. The verses containing the intercession of Canynge mayor of Bristol, and his ideas of the chiefest duties of a monarch are among the most touching and noble among their likes in all literature.

As a contributor to the Town and Country Magazine he obtained many a shilling, but far less often than what would have satisfied his eager wants, foremost among which was to see his mother and sister established in fine vestments and living in luxury. In time he grew to feel contempt for the Bristol people, high and low, and then he turned his eyes upon London. Application to Dodsley, the leading publisher, was discouraged for want of acquaintance with his condition and responsibility. He then essayed Horace Walpole, sending an ode on King Richard I. for his work "Anecdotes of Painting," and undertaking to furnish the names of several great painters, natives of Bristol. This application was signed "John Abbot of St. Austin's Minster, Bristol." In the letter he drew attention to the "Bristowe Tragedie" and other Rowlie poems. Walpole, who was as cold as urbane, expressed some curiosity to see these productions, which, when sent, he referred to Gray and Mason. These pronounced them forgeries. Whereupon Walpole, in the meantime informed of the real author and his condition, paid no further attention to the papers for a while, even to the request to return them. Enraged but undaunted by this failure he continued his work, both in old and contemporary English speech, producing "Aella," "Goddwyn," "Battle of Hastings," "Consuliad," "Revenge," etc. At length he grew restless to a degree beyond endurance. With the few acquaintances of his own age he talked of suicide. Feeling himself a stranger in that society, often spending whole nights in wakeful dreams instead of restful sleep, incensed with limitless ambition, he did indeed meditate upon making an end of himself. Among the papers on his desk one day was found his will, a singular document, containing among other things most incoherent bequests to several acquaintances, as of his "vigor and fire of youth" to George Catcall, the schoolmaster; "his humility" to the Rev. Mr. Camplin; his "prosody and grammar" and a "moiety" of his "modesty" to Mr. Burgum; concluding with directions to Paull Farr and John Flower, "at their own expense" to erect a monument upon his grave with this inscription: "To the memory of Thomas Chatterton. Reader, judge not. If thou art a Christian, believe that he shall be judged by a Supreme Power; to that power alone is he now answerable."

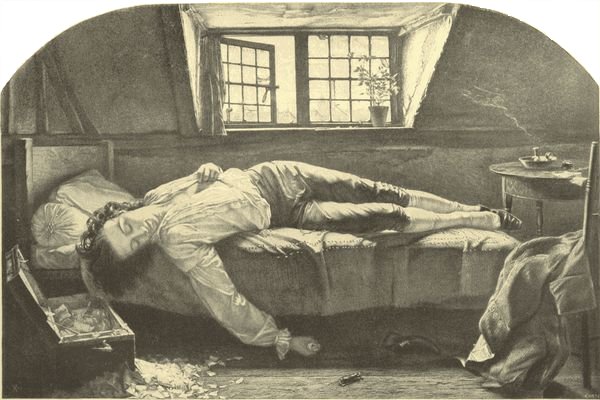

The Death of Chatterton, the Young Poet.

This document led to his dismissal by the attorney, who, in April 1770, returned to him his indentures. He at once set out for London with his manuscripts and a small sum of money raised by a few persons in Bristol. Through the help of a female relative he got board at the house of one Walmsley, a plasterer, in Shoreditch. In the history of literature nothing can be found so much to be compassionated as the life led by him during those summer months in the great city. Plodding the streets from day to day with his manuscripts, living mainly upon bread and water, not retiring to bed at night until near the morning, and then seldom closing his eyes, yet in this time guilty of no sort of known immorality, sending home frequent letters abounding in expressions of most fervid hopes and in promises of silks and other fine things to the objects of his affection, few cases could have appealed more piteously for help. The wits who might have succored were out of town. Goldsmith lamented that he had not known him. Johnson, with his stern kindness, if such a thing had been possible, could have saved him from despair. His deportment in the family with whom he lived was without exception of decorum, although he showed that any movement toward familiarity with him was offensive. In his sore stress he began to write papers upon politics, which were accepted by the partisan press. It was at the time when the arbitrary encroachments of George III. were met by the audacious courage of Mayor Beckford. Chatterton attached himself to the popular side; yet he seemed to have regret for the mistake in so doing, because of the comparative want of money in that party. In a long letter written to his sister, most of which is occupied with his great undertakings, he spoke thus of his political works:

"But the devil of the matter is, there is no money to be got on this side of the question. Interest is on the other side. But he is a poor author who cannot write on both sides. I believe I may be introduced (and if not I'll introduce myself) to a ruling power in the court party. I might have a recommendation to Sir George Colebrook, an East India director, as qualified for an office by no means despicable; but I shall not take a step to the sea whilst I can continue on land." In the midst of this struggle Beckford, the champion of popular rights, died suddenly, and the Walmsleys afterward testified that this event put Chatterton "perfectly out of his mind."

Soon after this he removed to Brook Street, Holborn, and became a boarder in the house of one Angell, a sack-maker. Here he continued to work day and night until desperation, long threatened, seized upon him. Court journals grew tired of articles showing little talent for political discussion, and he became ragged and almost shoeless. In the only despondent letter ever sent to his mother, he wrote of having stumbled into an open grave one day while walking in St. Pancras's Churchyard. The Angells, touched with his poverty and distress, kindly offered him food, which, except in one instance, he declined. One night after sitting with the family, apparently given over to despondency, he took affectionate leave of his hostess and the next morning was found dead from a dose of arsenic.

It was singular that the Rowlie writings were so far superior to his productions in modern English. The latter were commonplace, the former indicative of much genius. Indeed, one of the strongest evidences against their genuineness was the moral impossibility of their production in the age to which he assigned them. The imitation was as pathetic as it was audacious, attempted thus in honor of a model that never had existed.