The family of Petrarch was originally of Florence, where his ancestors held employments of trust and honour. Garzo, his great-grandfather, was a notary universally respected for his integrity and judgment. Though he had never devoted himself exclusively to letters, his literary opinion was consulted by men of learning. He lived to be a hundred and four years old, and died, like Plato, in the same bed in which he had been born.

Garzo left three sons, one of whom was the grandfather of Petrarch. Diminutives being customary to the Tuscan tongue, Pietro, the poet's father, was familiarly called Petracco, or little Peter. He, like his ancestors, was a notary, and not undistinguished for sagacity. He had several important commissions from government. At last, in the increasing conflicts between the Guelphs and the Ghibellines—or, as they now called themselves, the Blacks and the Whites—Petracco, like Dante, was obliged to fly from his native city, along with the other Florentines of the White party. He was unjustly accused of having officially issued a false deed, and was condemned, on the 20th of October, 1302, to pay a fine of one thousand lire, and to have his hand cut off, if that sum was not paid within ten days from the time he should be apprehended. Petracco fled, taking with him his wife, Eletta Canigiani, a lady of a distinguished family in Florence, several of whom had held the office of Gonfalonier.

Petracco and his wife first settled at Arezzo, a very ancient city of Tuscany. Hostilities did not cease between the Florentine factions till some years afterwards; and, in an attempt made by the Whites to take Florence by assault, Petracco was present with his party. They were repulsed. This action, which was fatal to their cause, took place in the night between the 19th and 20th days of July, 1304,—the precise date of the birth of Petrarch.

During our poet's infancy, his family had still to struggle with[Pg x] an adverse fate; for his proscribed and wandering father was obliged to separate himself from his wife and child, in order to have the means of supporting them.

As the pretext for banishing Petracco was purely personal, Eletta, his wife, was not included in the sentence. She removed to a small property of her husband's, at Ancisa, fourteen miles from Florence, and took the little poet along with her, in the seventh month of his age. In their passage thither, both mother and child, together with their guide, had a narrow escape from being drowned in the Arno. Eletta entrusted her precious charge to a robust peasant, who, for fear of hurting the child, wrapt it in a swaddling cloth, and suspended it over his shoulder, in the same manner as Metabus is described by Virgil, in the eleventh book of the Æneid, to have carried his daughter Camilla. In passing the river, the horse of the guide, who carried Petrarch, stumbled, and sank down; and in their struggles to save him, both his sturdy bearer and the frantic parent were, like the infant itself, on the point of being drowned.

After Eletta had settled at Ancisa, Petracco often visited her by stealth, and the pledges of their affection were two other sons, one of whom died in childhood. The other, called Gherardo, was educated along with Petrarch. Petrarch remained with his mother at Ancisa for seven years.

The arrival of the Emperor, Henry VII., in Italy, revived the hopes of the banished Florentines; and Petracco, in order to wait the event, went to Pisa, whither he brought his wife and Francesco, who was now in his eighth year. Petracco remained with his family in Pisa for several months; but tired at last of fallacious hopes, and not daring to trust himself to the promises of the popular party, who offered to recall him to Florence, he sought an asylum in Avignon, a place to which many Italians were allured by the hopes of honours and gain at the papal residence. In this voyage, Petracco and his family were nearly shipwrecked off Marseilles.

But the numbers that crowded to Avignon, and its luxurious court, rendered that city an uncomfortable place for a family in slender circumstances. Petracco accordingly removed his household, in 1315, to Carpentras, a small quiet town, where living was cheaper than at Avignon. There, under the care of his mother, Petrarch imbibed his first instruction, and was taught by one Convennole da Prato as much grammar and logic as could be learned at his age, and more than could be learned by an ordinary disciple from so common-place a preceptor. This poor master, however, had sufficient intelligence to appreciate the genius of Petrarch, whom he esteemed and honoured beyond all his other pupils. On the other hand, his illustrious scholar aided him, in his old age and poverty, out of his scanty income.

Petrarch used to compare Convennole to a whetstone, which is[Pg xi] blunt itself, but which sharpens others. His old master, however was sharp enough to overreach him in the matter of borrowing and lending. When the poet had collected a considerable library, Convennole paid him a visit, and, pretending to be engaged in something that required him to consult Cicero, borrowed a copy of one of the works of that orator, which was particularly valuable. He made excuses, from time to time, for not returning it; but Petrarch, at last, had too good reason to suspect that the old grammarian had pawned it. The poet would willingly have paid for redeeming it, but Convennole was so much ashamed, that he would not tell to whom it was pawned; and the precious manuscript was lost.

Petracco contracted an intimacy with Settimo, a Genoese, who was like himself, an exile for his political principles, and who fixed his abode at Avignon with his wife and his boy, Guido Settimo, who was about the same age with Petrarch. The two youths formed a friendship, which subsisted between them for life.

Petrarch manifested signs of extraordinary sensibility to the charms of nature in his childhood, both when he was at Carpentras and at Avignon. One day, when he was at the latter residence, a party was made up, to see the fountain of Vaucluse, a few leagues from Avignon. The little Francesco had no sooner arrived at the lovely landscape than he was struck with its beauties, and exclaimed, "Here, now, is a retirement suited to my taste, and preferable, in my eyes, to the greatest and most splendid cities."

A genius so fine as that of our poet could not servilely confine itself to the slow method of school learning, adapted to the intellects of ordinary boys. Accordingly, while his fellow pupils were still plodding through the first rudiments of Latin, Petrarch had recourse to the original writers, from whom the grammarians drew their authority, and particularly employed himself in perusing the works of Cicero. And, although he was, at this time, much too young to comprehend the full force of the orator's reasoning, he was so struck with the charms of his style, that he considered him the only true model in prose composition.

His father, who was himself something of a scholar, was pleased and astonished at this early proof of his good taste; he applauded his classical studies, and encouraged him to persevere in them; but, very soon, he imagined that he had cause to repent of his commendations. Classical learning was, in that age, regarded as a mere solitary accomplishment, and the law was the only road that led to honours and preferment. Petracco was, therefore, desirous to turn into that channel the brilliant qualities of his son; and for this purpose he sent him, at the age of fifteen, to the university of Montpelier. Petrarch remained there for four years, and attended lectures on law from some of[Pg xii] the most famous professors of the science. But his prepossession for Cicero prevented him from much frequenting the dry and dusty walks of jurisprudence. In his epistle to posterity, he endeavours to justify this repugnance by other motives. He represents the abuses, the chicanery, and mercenary practices of the law, as inconsistent with every principle of candour and honesty.

When Petracco observed that his son made no great progress in his legal studies at Montpelier, he removed him, in 1323, to Bologna, celebrated for the study of the canon and civil law, probably imagining that the superior fame of the latter place might attract him to love the law. To Bologna Petrarch was accompanied by his brother Gherardo, and by his inseparable friend, young Guido Settimo.

But neither the abilities of the several professors in that celebrated academy, nor the strongest exhortations of his father, were sufficient to conquer the deeply-rooted aversion which our poet had conceived for the law. Accordingly, Petracco hastened to Bologna, that he might endeavour to check his son's indulgence in literature, which disconcerted his favourite designs. Petrarch, guessing at the motive of his arrival, hid the copies of Cicero, Virgil, and some other authors, which composed his small library, and to purchase which he had deprived himself of almost the necessaries of life. His father, however, soon discovered the place of their concealment, and threw them into the fire. Petrarch exhibited as much agony as if he had been himself the martyr of his father's resentment. Petracco was so much affected by his son's tears, that he rescued from the flames Cicero and Virgil, and, presenting them to Petrarch, he said, "Virgil will console you for the loss of your other MSS., and Cicero will prepare you for the study of the law."

It is by no means wonderful that a mind like Petrarch's could but ill relish the glosses of the Code and the commentaries on the Decretals.

At Bologna, however, he met with an accomplished literary man and no inelegant poet in one of the professors, who, if he failed in persuading Petrarch to make the law his profession, certainly quickened his relish and ambition for poetry. This man was Cino da Pistoia, who is esteemed by Italians as the most tender and harmonious lyric poet in the native language anterior to Petrarch.

During his residence at Bologna, Petrarch made an excursion as far as Venice, a city that struck him with enthusiastic admiration. In one of his letters he calls it "orbem alterum." Whilst Italy was harassed, he says, on all sides by continual dissensions, like the sea in a storm, Venice alone appeared like a safe harbour, which overlooked the tempest without feeling its commotion. The resolute and independent spirit of that republic made an[Pg xiii] indelible impression on Petrarch's heart. The young poet, perhaps, at this time little imagined that Venice was to be the last scene of his triumphant eloquence.

Soon after his return from Venice to Bologna, he received the melancholy intelligence of the death of his mother, in the thirty-eighth year of her age. Her age is known by a copy of verses which Petrarch wrote upon her death, the verses being the same in number as the years of her life. She had lived humble and retired, and had devoted herself to the good of her family; virtuous amidst the prevalence of corrupted manners, and, though a beautiful woman, untainted by the breath of calumny. Petrarch has repaid her maternal affection by preserving her memory from oblivion. Petracco did not long survive the death of this excellent woman. According to the judgment of our poet, his father was a man of strong character and understanding. Banished from his native country, and engaged in providing for his family, he was prevented by the scantiness of his fortune, and the cares of his situation, from rising to that eminence which he might have otherwise attained. But his admiration of Cicero, in an age when that author was universally neglected, was a proof of his superior mind.

Petrarch quitted Bologna upon the death of his father, and returned to Avignon, with his brother Gherardo, to collect the shattered remains of their father's property. Upon their arrival, they found their domestic affairs in a state of great disorder, as the executors of Petracco's will had betrayed the trust reposed in them, and had seized most of the effects of which they could dispose. Under these circumstances, Petrarch was most anxious for a MS. of Cicero, which his father had highly prized. "The guardians," he writes, "eager to appropriate what they esteemed the more valuable effects, had fortunately left this MS. as a thing of no value." Thus he owed to their ignorance this treatise, which he considered the richest portion of the inheritance left him by his father.

But, that inheritance being small, and not sufficient for the maintenance of the two brothers, they were obliged to think of some profession for their subsistence; they therefore entered the church; and Avignon was the place, of all others, where preferment was most easily obtained. John XXII. had fixed his residence entirely in that city since October, 1316, and had appropriated to himself the nomination to all the vacant benefices. The pretence for this appropriation was to prevent simony—in others, not in his Holiness—as the sale of benefices was carried by him to an enormous height. At every promotion to a bishopric, he removed other bishops; and, by the meanest impositions, soon amassed prodigious wealth. Scandalous emoluments, also, which arose from the sale of indulgences, were enlarged, if not invented, under his papacy, and every method of acquiring riches[Pg xiv] was justified which could contribute to feed his avarice. By these sordid means, he collected such sums, that, according to Villani, he left behind him, in the sacred treasury, twenty-five millions of florins, a treasure which Voltaire remarks is hardly credible.

The luxury and corruption which reigned in the Roman court at Avignon are fully displayed in some letters of Petrarch's, without either date or address. The partizans of that court, it is true, accuse him of prejudice and exaggeration. He painted, as they allege, the popes and cardinals in the gloomiest colouring. His letters contain the blackest catalogue of crimes that ever disgraced humanity.

Petrarch was twenty-two years of age when he settled at Avignon, a scene of licentiousness and profligacy. The luxury of the cardinals, and the pomp and riches of the papal court, were displayed in an extravagant profusion of feasts and ceremonies, which attracted to Avignon women of all ranks, among whom intrigue and gallantry were generally countenanced. Petrarch was by nature of a warm temperament, with vivid and susceptible passions, and strongly attached to the fair sex. We must not therefore be surprised if, with these dispositions, and in such a dissolute city, he was betrayed into some excesses. But these were the result of his complexion, and not of deliberate profligacy. He alludes to this subject in his Epistle to Posterity, with every appearance of truth and candour.

From his own confession, Petrarch seems to have been somewhat vain of his personal appearance during his youth, a venial foible, from which neither the handsome nor the homely, nor the wise nor the foolish, are exempt. It is amusing to find our own Milton betraying this weakness, in spite of all the surrounding strength of his character. In answering one of his slanderers, who had called him pale and cadaverous, the author of Paradise Lost appeals to all who knew him whether his complexion was not so fresh and blooming as to make him appear ten years younger than he really was.

Petrarch, when young, was so strikingly handsome, that he was frequently pointed at and admired as he passed along, for his features were manly, well-formed, and expressive, and his carriage was graceful and distinguished. He was sprightly in conversation, and his voice was uncommonly musical. His complexion was between brown and fair, and his eyes were bright and animated. His countenance was a faithful index of his heart.

He endeavoured to temper the warmth of his constitution by the regularity of his living and the plainness of his diet. He indulged little in either wine or sleep, and fed chiefly on fruits and vegetables.

In his early days he was nice and neat in his dress, even to a degree of affectation, which, in later life, he ridiculed when writing to his brother Gherardo. "Do you remember," he says,[Pg xv] "how much care we employed in the lure of dressing our persons; when we traversed the streets, with what attention did we not avoid every breath of wind which might discompose our hair; and with what caution did we not prevent the least speck of dirt from soiling our garments!"

This vanity, however, lasted only during his youthful days. And even then neither attention to his personal appearance, nor his attachment to the fair sex, nor his attendance upon the great, could induce Petrarch to neglect his own mental improvement, for, amidst all these occupations, he found leisure for application, and devoted himself to the cultivation of his favourite pursuits of literature.

Inclined by nature to moral philosophy, he was guided by the reading of Cicero and Seneca to that profound knowledge of the human heart, of the duties of others and of our own duties, which shows itself in all his writings. Gifted with a mind full of enthusiasm for poetry, he learned from Virgil elegance and dignity in versification. But he had still higher advantages from the perusal of Livy. The magnanimous actions of Roman heroes so much excited the soul of Petrarch, that he thought the men of his own age light and contemptible.

His first compositions were in Latin: many motives, however, induced him to compose in the vulgar tongue, as Italian was then called, which, though improved by Dante, was still, in many respects, harsh and inelegant, and much in want of new beauties. Petrarch wrote for the living, and for that portion of the living who were least of all to be fascinated by the language of the dead. Latin might be all very well for inscriptions on mausoleums, but it was not suited for the ears of beauty and the bowers of love. The Italian language acquired, under his cultivation, increased elegance and richness, so that the harmony of his style has contributed to its beauty. He did not, however, attach himself solely to Italian, but composed much in Latin, which he reserved for graver, or, as he considered, more important subjects. His compositions in Latin are—Africa, an epic poem; his Bucolics, containing twelve eclogues; and three books of epistles.

Petrarch's greatest obstacles to improvement arose from the scarcity of authors whom he wished to consult—for the manuscripts of the writers of the Augustan age were, at that time, so uncommon, that many could not be procured, and many more of them could not be purchased under the most extravagant price. This scarcity of books had checked the dawning light of literature. The zeal of our poet, however, surmounted all these obstacles, for he was indefatigable in collecting and copying many of the choicest manuscripts; and posterity is indebted to him for the possession of many valuable writings, which were in danger of being lost through the carelessness or ignorance of the possessors.[Pg xvi]

Petrarch could not but perceive the superiority of his own understanding and the brilliancy of his abilities. The modest humility which knows not its own worth is not wont to show itself in minds much above mediocrity; and to elevated geniuses this virtue is a stranger. Petrarch from his youthful age had an internal assurance that he should prove worthy of estimation and honours. Nevertheless, as he advanced in the field of science, he saw the prospect increase, Alps over Alps, and seemed to be lost amidst the immensity of objects before him. Hence the anticipation of immeasurable labours occasionally damped his application. But from this depression of spirits he was much relieved by the encouragement of John of Florence, one of the secretaries of the Pope, a man of learning and probity. He soon distinguished the extraordinary abilities of Petrarch; he directed him in his studies, and cheered up his ambition. Petrarch returned his affection with unbounded confidence. He entrusted him with all his foibles, his disgusts, and his uneasinesses. He says that he never conversed with him without finding himself more calm and composed, and more animated for study.

The superior sagacity of our poet, together with his pleasing manners, and his increasing reputation for knowledge, ensured to him the most flattering prospects of success. His conversation was courted by men of rank, and his acquaintance was sought by men of learning. It was at this time, 1326, that his merit procured him the friendship and patronage of James Colonna, who belonged to one of the most ancient and illustrious families of Italy.

"About the twenty-second year of my life," Petrarch writes to one of his friends, "I became acquainted with James Colonna. He had seen me whilst I resided at Bologna, and was prepossessed, as he was pleased to say, with my appearance. Upon his arrival at Avignon, he again saw me, when, having inquired minutely into the state of my affairs, he admitted me to his friendship. I cannot sufficiently describe the cheerfulness of his temper, his social disposition, his moderation in prosperity, his constancy in adversity. I speak not from report, but from my own experience. He was endowed with a persuasive and forcible eloquence. His conversation and letters displayed the amiableness of his sincere character. He gained the first place in my affections, which he ever afterwards retained."

Such is the portrait which our poet gives of James Colonna. A faithful and wise friend is among the most precious gifts of fortune; but, as friendships cannot wholly feed our affections, the heart of Petrarch, at this ardent age, was destined to be swayed by still tenderer feelings. He had nearly finished his twenty-third year without having ever seriously known the passion of love. In that year he first saw Laura. Concerning this lady, at one time, when no life of Petrarch had been yet written that was[Pg xvii] not crude and inaccurate, his biographers launched into the wildest speculations. One author considered her as an allegorical being; another discovered her to be a type of the Virgin Mary; another thought her an allegory of poetry and repentance. Some denied her even allegorical existence, and deemed her a mere phantom beauty, with which the poet had fallen in love, like Pygmalion with the work of his own creation. All these caprices about Laura's history have been long since dissipated, though the principal facts respecting her were never distinctly verified, till De Sade, her own descendant, wrote his memoirs of the Life of Petrarch.

Petrarch himself relates that in 1327, exactly at the first hour of the 6th of April, he first beheld Laura in the church of St. Clara of Avignon,[A] where neither the sacredness of the place, nor the solemnity of the day, could prevent him from being smitten for life with human love. In that fatal hour he saw a lady, a little younger than himself[B] in a green mantle sprinkled with violets, on which her golden hair fell plaited in tresses. She was distinguished from all others by her proud and delicate carriage. The impression which she made on his heart was sudden, yet it was never effaced.

Laura, descended from a family of ancient and noble extraction, was the daughter of Audibert de Noves, a Provençal nobleman, by his wife Esmessenda. She was born at Avignon, probably in 1308. She had a considerable fortune, and was married in 1325 to Hugh de Sade. The particulars of her life are little known, as Petrarch has left few traces of them in his letters; and it was still less likely that he should enter upon her personal history in his sonnets, which, as they were principally addressed to herself, made it unnecessary for him to inform her of what she already knew.

While many writers have erred in considering Petrarch's attachment as visionary, others, who have allowed the reality of his passion, have been mistaken in their opinion of its object. They allege that Petrarch was a happy lover, and that his mistress was accustomed to meet him at Vaucluse, and make him a full compensation for his fondness. No one at all acquainted with the life and writings of Petrarch will need to be told that this is an absurd fiction. Laura, a married woman, who bore ten children to a rather morose husband, could not have gone to meet him at Vaucluse without the most flagrant scandal. It is evident from his writings that she repudiated his passion whenever it threatened to exceed the limits of virtuous friendship. On one occasion,[Pg xviii] when he seemed to presume too far upon her favour, she said to him with severity, "I am not what you take me for." If his love had been successful, he would have said less about it.

Of the two persons in this love affair, I am more inclined to pity Laura than Petrarch. Independently of her personal charms, I cannot conceive Laura otherwise than as a kind-hearted, loveable woman, who could not well be supposed to be totally indifferent to the devotion of the most famous and fascinating man of his age. On the other hand, what was the penalty that she would have paid if she had encouraged his addresses as far as he would have carried them? Her disgrace, a stigma left on her family, and the loss of all that character which upholds a woman in her own estimation and in that of the world. I would not go so far as to say that she did not at times betray an anxiety to retain him under the spell of her fascination, as, for instance, when she is said to have cast her eyes to the ground in sadness when he announced his intention to leave Avignon; but still I should like to hear her own explanation before I condemned her. And, after all, she was only anxious for the continuance of attentions, respecting which she had made a fixed understanding that they should not exceed the bounds of innocence.

We have no distinct account how her husband regarded the homage of Petrarch to his wife—whether it flattered his vanity, or moved his wrath. As tradition gives him no very good character for temper, the latter supposition is the more probable. Every morning that he went out he might hear from some kind friend the praises of a new sonnet which Petrarch had written on his wife; and, when he came back to dinner, of course his good humour was not improved by the intelligence. He was in the habit of scolding her till she wept; he married seven months after her death, and, from all that is known of him, appears to have been a bad husband. I suspect that Laura paid dearly for her poet's idolatry.

No incidents of Petrarch's life have been transmitted to us for the first year or two after his attachment to Laura commenced. He seems to have continued at Avignon, prosecuting his studies and feeding his passion.

James Colonna, his friend and patron, was promoted in 1328 to the bishopric of Lombes in Gascony; and in the year 1330 he went from Avignon to take possession of his diocese, and invited Petrarch to accompany him to his residence. No invitation could be more acceptable to our poet: they set out at the end of March, 1330. In order to reach Lombes, it was necessary to cross the whole of Languedoc, and to pass through Montpelier, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Petrarch already knew Montpelier, where he had, or ought to have, studied the law for four years.

Full of enthusiasm for Rome, Petrarch was rejoiced to find at Narbonne the city which had been the first Roman colony planted[Pg xix] among the Gauls. This colony had been formed entirely of Roman citizens, and, in order to reconcile them to their exile, the city was built like a little image of Rome. It had its capital, its baths, arches, and fountains; all which works were worthy of the Roman name. In passing through Narbonne, Petrarch discovered a number of ancient monuments and inscriptions.

Our travellers thence proceeded to Toulouse, where they passed several days. This city, which was known even before the foundation of Rome, is called, in some ancient Roman acts, "Roma Garumnæ." It was famous in the classical ages for cultivating literature. After the fall of the Roman empire, the successive incursions of the Visigoths, the Saracens, and the Normans, for a long time silenced the Muses at Toulouse; but they returned to their favourite haunt after ages of barbarism had passed away. De Sade says, that what is termed Provençal poetry was much more cultivated by the Languedocians than by the Provençals, properly so called. The city of Toulouse was considered as the principal seat of this earliest modern poetry, which was carried to perfection in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, under the patronage of the Counts of Toulouse, particularly Raimond V., and his son, Raimond VI. Petrarch speaks with high praise of those poets in his Triumphs of Love. It has been alleged that he owed them this mark of his regard for their having been so useful to him in his Italian poetry; and Nostradamus even accuses him of having stolen much from them. But Tassoni, who understood the Provençal poets better than Nostradamus, defends him successfully from this absurd accusation.

Although Provençal poetry was a little on its decline since the days of the Dukes of Aquitaine and the Counts of Toulouse, it was still held in honour; and, when Petrarch arrived, the Floral games had been established at Toulouse during six years.[C]

Ere long, however, our travellers found less agreeable objects of curiosity, that formed a sad contrast with the chivalric manners, the floral games, and the gay poetry of southern France. Bishop Colonna and Petrarch had intended to remain for some time at Toulouse; but their sojourn was abridged by their horror at a tragic event[D] in the principal monastery of the place. There[Pg xx] lived in that monastery a young monk, named Augustin, who was expert in music, and accompanied the psalmody of the religious brothers with beautiful touches on the organ. The superior of the convent, relaxing its discipline, permitted Augustin frequently to mix with the world, in order to teach music, and to improve himself in the art. The young monk was in the habit of familiarly visiting the house of a respectable citizen: he was frequently in the society of his daughter, and, by the express encouragement of her father, undertook to exercise her in the practice of music. Another young man, who was in love with the girl, grew jealous of the monk, who was allowed to converse so familiarly with her, whilst he, her lay admirer, could only have stolen glimpses of her as she passed to church or to public spectacles. He set about the ruin of his supposed rival with cunning atrocity; and, finding that the young woman was infirm in health, suborned a physician, as worthless as himself, to declare that she was pregnant. Her credulous father, without inquiring whether the intelligence was true or false, went to the superior of the convent, and accused Augustin, who, though thunderstruck at the accusation, denied it firmly, and defended himself intrepidly. But the superior was deaf to his plea of innocence, and ordered him to be shut up in his cell, that he might await his punishment. Thither the poor young man was conducted, and threw himself on his bed in a state of horror.

The superior and the elders among the friars thought it a meet fate for the accused that he should be buried alive in a subterranean dungeon, after receiving the terrific sentence of "Vade in pace." At the end of several days the victim dashed out his brains against the walls of his sepulchre. Bishop Colonna, who, it would appear, had no power to oppose this hideous transaction, when he was informed of it, determined to leave the place immediately; and Petrarch in his indignation exclaimed—

"Heu! fuge crudeles terras, fuge littus avarum."—Virg.

On the 26th of May, 1330, the Bishop of Lombes and Petrarch quitted Toulouse, and arrived at the mansion of the diocese. Lombes—in Latin, Lombarium—lies at the foot of the Pyrenees, only eight leagues from Toulouse. It is small and ill-built, and offers no allurement to the curiosity of the traveller. Till lately it had been a simple abbey of the Augustine monks. The whole of the clergy of the little city, singing psalms, issued out of Lombes to meet their new pastor, who, under a rich canopy, was conducted to the principal church, and there, in his episcopal robes, blessed the people, and delivered an eloquent discourse. Petrarch beheld with admiration the dignified behaviour of the youthful prelate. James Colonna, though accustomed to the wealth and luxury of Rome, came to the Pyrenean rocks with a pleased countenance. "His aspect," says Petrarch, "made it seem as if Italy had been[Pg xxi] transported into Gascony." Nothing is more beautiful than the patient endurance of our destiny; yet there are many priests who would suffer translation to a well-paid, though mountainous bishopric, with patience and piety.

The vicinity of the Pyrenees renders the climate of Lombes very severe; and the character and conversation of the inhabitants were scarcely more genial than their climate. But Petrarch found in the bishop's abode friends who consoled him in this exile among the Lombesians. Two young and familiar inmates of the Bishop's house attracted and returned his attachment. The first of these was Lello di Stefani, a youth of a noble and ancient family in Rome, long attached to the Colonnas. Lello's gifted understanding was improved by study; so Petrarch tells us; and he could have been no ordinary man whom our accomplished poet so highly valued. In his youth he had quitted his studies for the profession of arms; but the return of peace restored him to his literary pursuits. Such was the attachment between Petrarch and Lello, that Petrarch gave him the name of Lælius, the most attached companion of Scipio. The other friend to whom Petrarch attached himself in the house of James Colonna was a young German, extremely accomplished in music. De Sade says that his name was Louis, without mentioning his cognomen. He was a native of Ham, near Bois le Duc, on the left bank of the Rhine between Brabant and Holland. Petrarch, with his Italian prejudices, regarded him as a barbarian by birth; but he was so fascinated by his serene temper and strong judgment, that he singled him out to be the chief of all his friends, and gave him the name of Socrates, noting him as an example that Nature can sometimes produce geniuses in the most unpropitious regions.

After having passed the summer of 1330 at Lombes, the Bishop returned to Avignon, in order to meet his father, the elder Stefano Colonna, and his brother the Cardinal.

The Colonnas were a family of the first distinction in modern Italy. They had been exceedingly powerful during the popedom of Boniface VIII., through the talents of the late Cardinal James Colonna, brother of the famous old Stefano, so well known to Petrarch, and whom he used to call a phœnix sprung up from the ashes of Rome. Their house possessed also an influential public character in the Cardinal Pietro, brother of the younger Stefano. They were formidable from the territories and castles which they possessed, and by their alliance and friendship with Charles, King of Naples. The power of the Colonna family became offensive to Boniface, who, besides, hated the two Cardinals for having opposed the renunciation of Celestine V., which Boniface had fraudulently obtained. Boniface procured a crusade against them. They were beaten, expelled from their castles, and almost exterminated; they implored peace, but in vain; they were driven from Rome, and obliged to seek refuge, some in Sicily[Pg xxii] and others in France. During the time of their exile, Boniface proclaimed it a capital crime to give shelter to any of them.

The Colonnas finally returned to their dignities and property, and afterwards made successful war against the house of their rivals, the Orsini.

John Colonna, the Cardinal, brother of the Bishop of Lombes, and son of old Stefano, was one of the very ablest men at the papal court. He insisted on our poet taking up his abode in his own palace at Avignon. "What good fortune was this for me!" says Petrarch. "This great man never made me feel that he was my superior in station. He was like a father or an indulgent brother; and I lived in his house as if it had been my own." At a subsequent period, we find him on somewhat cooler terms with John Colonna, and complaining that his domestic dependence had, by length of time, become wearisome to him. But great allowance is to be made for such apparent inconsistencies in human attachment. At different times our feelings and language on any subject may be different without being insincere. The truth seems to be that Petrarch looked forward to the friendship of the Colonnas for promotion, which he either received scantily, or not at all; so it is little marvellous if he should have at last felt the tedium of patronage.

For the present, however, this home was completely to Petrarch's taste. It was the rendezvous of all strangers distinguished by their knowledge and talents, whom the papal court attracted to Avignon, which was now the great centre of all political negotiations.

This assemblage of the learned had a powerful influence on Petrarch's fine imagination. He had been engaged for some time in the perusal of Livy, and his enthusiasm for ancient Rome was heightened, if possible, by the conversation of old Stefano Colonna, who dwelt on no subject with so much interest as on the temples and palaces of the ancient city, majestic even in their ruins.

During the bitter persecution raised against his family by Boniface VIII., Stefano Colonna had been the chief object of the Pope's implacable resentment. Though oppressed by the most adverse circumstances, his estates confiscated, his palaces levelled with the ground, and himself driven into exile, the majesty of his appearance, and the magnanimity of his character, attracted the respect of strangers wherever he went. He had the air of a sovereign prince rather than of an exile, and commanded more regard than monarchs in the height of their ostentation.

In the picture of his times, Stefano makes a noble and commanding figure. If the reader, however, happens to search into that period of Italian history, he will find many facts to cool the romance of his imagination respecting all the Colonna family. They were, in plain truth, an oppressive aristocratic family. The portion of Italy which they and their tyrannical rivals possessed[Pg xxiii] was infamously governed. The highways were rendered impassable by banditti, who were in the pay of contesting feudal lords; and life and property were everywhere insecure.

Stefano, nevertheless, seems to have been a man formed for better times. He improved in the school of misfortune—the serenity of his temper remained unclouded by adversity, and his faculties unimpaired by age.

Among the illustrious strangers who came to Avignon at this time was our countryman, Richard de Bury, then accounted the most learned man of England. He arrived at Avignon in 1331, having been sent to the Pope by Edward III. De Sade conceives that the object of his embassy was to justify his sovereign before the Pontiff for having confined the Queen-mother in the castle of Risings, and for having caused her favourite, Roger de Mortimer, to be hanged. It was a matter of course that so illustrious a stranger as Richard de Bury should be received with distinction by Cardinal Colonna. Petrarch eagerly seized the opportunity of forming his acquaintance, confident that De Bury could give him valuable information on many points of geography and history. They had several conversations. Petrarch tells us that he entreated the learned Englishman to make him acquainted with the true situation of the isle of Thule, of which the ancients speak with much uncertainty, but which their best geographers place at the distance of some days' navigation from the north of England. De Bury was, in all probability, puzzled with the question, though he did not like to confess his ignorance. He excused himself by promising to inquire into the subject as soon as he should get back to his books in England, and to write to him the best information he could afford. It does not appear, however, that he performed his promise.

De Bury's stay at the court of Avignon was very short. King Edward, it is true, sent him a second time to the Pope, two years afterwards, on important business. The seeds of discord between France and England began to germinate strongly, and that circumstance probably occasioned De Bury's second mission. Unfortunately, however, Petrarch could not avail himself of his return so as to have further interviews with the English scholar. Petrarch wrote repeatedly to De Bury for his promised explanations respecting Thule; but, whether our countryman had found nothing in his library to satisfy his inquiries, or was prevented by his public occupations, there is no appearance of his having ever answered Petrarch's letters.

Stephano Colonna the younger had brought with him to Avignon his son Agapito, who was destined for the church, that he might be educated under the eyes of the Cardinal and the Bishop, who were his uncles. These two prelates joined with their father in entreating Petrarch to undertake the superintendence of Agapito's studies. Our poet, avaricious of his time, and jealous of his inde[Pg xxiv]pendence, was at first reluctant to undertake the charge; but, from his attachment to the family, at last accepted it. De Sade tells us that Petrarch was not successful in the young man's education; and, from a natural partiality for the hero of his biography, lays the blame on his pupil. At the same time he acknowledges that a man with poetry in his head and love in his heart was not the most proper mentor in the world for a youth who was to be educated for the church. At this time, Petrarch's passion for Laura continued to haunt his peace with incessant violence. She had received him at first with good-humour and affability; but it was only while he set strict bounds to the expression of his attachment. He had not, however, sufficient self-command to comply with these terms. His constant assiduities, his eyes continually riveted upon her, and the wildness of his looks, convinced her of his inordinate attachment; her virtue took alarm; she retired whenever he approached her, and even covered her face with a veil whilst he was present, nor would she condescend to the slightest action or look that might seem to countenance his passion.

Petrarch complains of these severities in many of his melancholy sonnets. Meanwhile, if fame could have been a balm to love, he might have been happy. His reputation as a poet was increasing, and his compositions were read with universal approbation.

The next interesting event in our poet's life was a larger course of travels, which he took through the north of France, through Flanders, Brabant, and a part of Germany, subsequently to his tour in Languedoc. Petrarch mentions that he undertook this journey about the twenty-fifth year of his age. He was prompted to travel not only by his curiosity to observe men and manners, by his desire of seeing monuments of antiquity, and his hopes of discovering the MSS. of ancient authors, but also, we may believe, by his wish, if it were possible, to escape from himself, and to forget Laura.

From Paris Petrarch wrote as follows to Cardinal Colonna. "I have visited Paris, the capital of the whole kingdom of France. I entered it in the same state of mind that was felt by Apuleias when he visited Hypata, a city of Thessaly, celebrated for its magic, of which such wonderful things were related, looking again and again at every object, in solicitous suspense, to know whether all that he had heard of the far-famed place was true or false. Here I pass a great deal of time in observation, and, as the day is too short for my curiosity, I add the night. At last, it seems to me that, by long exploring, I have enabled myself to distinguish between the true and the false in what is related about Paris. But, as the subject would be too tedious for this occasion, I shall defer entering fully into particulars till I can do so vivâ voce. My impatience, however, impels me to sketch for you briefly a general idea of this so celebrated city, and of the character of its inhabitants.[Pg xxv]

"Paris, though always inferior to its fame, and much indebted to the lies of its own people, is undoubtedly a great city. To be sure I never saw a dirtier place, except Avignon. At the same time, its population contains the most learned of men, and it is like a great basket in which are collected the rarest fruits of every country. From the time that its university was founded, as they say by Alcuin, the teacher of Charlemagne, there has not been, to my knowledge, a single Parisian of any fame. The great luminaries of the university were all strangers; and, if the love of my country does not deceive me, they were chiefly Italians, such as Pietro Lombardo, Tomaso d'Aquino, Bonaventura, and many others.

"The character of the Parisians is very singular. There was a time when, from the ferocity of their manners, the French were reckoned barbarians. At present the case is wholly changed. A gay disposition, love of society, ease, and playfulness in conversation now characterize them. They seek every opportunity of distinguishing themselves; and make war against all cares with joking, laughing, singing, eating, and drinking. Prone, however, as they are to pleasure, they are not heroic in adversity. The French love their country and their countrymen; they censure with rigour the faults of other nations, but spread a proportionably thick veil over their own defects."

From Paris, Petrarch proceeded to Ghent, of which only he makes mention to the Cardinal, without noticing any of the towns that lie between. It is curious to find our poet out of humour with Flanders on account of the high price of wine, which was not an indigenous article. In the latter part of his life, Petrarch was certainly one of the most abstemious of men; but, at this period, it would seem that he drank good liquor enough to be concerned about its price.

From Ghent he passed on to Liege. "This city is distinguished," he says, "by the riches and the number of its clergy. As I had heard that excellent MSS. might be found there, I stopped in the place for some time. But is it not singular that in so considerable a place I had difficulty to procure ink enough to copy two orations of Cicero's, and the little that I could obtain was as yellow as saffron?"

Petrarch was received at most of the places he visited, and more particularly at Cologne, with marks of great respect; and he was agreeably surprised to find that his reputation had acquired him the partiality and acquaintance of several inhabitants. He was conducted by his new friends to the banks of the Rhine, where the inhabitants were engaged in the performance of a superstitious annual ceremony, which, for its singularity, deserves to be recorded.

"The banks of the river were crowded with a considerable number of women, their persons comely, and their dress elegant.[Pg xxvi] This great concourse of people seemed to create no confusion. A number of these women, with cheerful countenances, crowned with flowers, bathed their hands and arms in the stream, and uttered, at the same time, some harmonious expressions in a language which I did not understand. I inquired into the cause of this ceremony, and was informed that it arose from a tradition among the people, and particularly among the women, that the impending calamities of the year were carried away by this ablution, and that blessings succeeded in their place. Hence this ceremony is annually renewed, and the ablution performed with unremitting diligence."

The ceremony being finished, Petrarch smiled at their superstition, and exclaimed, "O happy inhabitants of the Rhine, whose waters wash out your miseries, whilst neither the Po nor the Tiber can wash out ours! You transmit your evils to the Britons by means of this river, whilst we send off ours to the Illyrians and the Africans. It seems that our rivers have a slower course."

Petrarch shortened his excursion that he might return the sooner to Avignon, where the Bishop of Lombes had promised to await his return, and take him to Rome.

When he arrived at Lyons, however, he was informed that the Bishop had departed from Avignon for Rome. In the first paroxysm of his disappointment he wrote a letter to his friend, which portrays strongly affectionate feelings, but at the same time an irascible temper. When he came to Avignon, the Cardinal Colonna relieved him from his irritation by acquainting him with the real cause of his brother's departure. The flames of civil dissension had been kindled at Rome between the rival families of Colonna and Orsini. The latter had made great preparations to carry on the war with vigour. In this crisis of affairs, James Colonna had been summoned to Rome to support the interests of his family, and, by his courage and influence, to procure them the succour which they so much required.

Petrarch continued to reside at Avignon for several years after returning from his travels in France and Flanders. It does not appear from his sonnets, during those years, either that his passion for Laura had abated, or that she had given him any more encouragement than heretofore. But in the year 1334, an accident renewed the utmost tenderness of his affections. A terrible affliction visited the city of Avignon. The heat and the drought were so excessive that almost the whole of the common people went about naked to the waist, and, with frenzy and miserable cries, implored Heaven to put an end to their calamities. Persons of both sexes and of all ages had their bodies covered with scales, and changed their skins like serpents.

Laura's constitution was too delicate to resist this infectious malady, and her illness greatly alarmed Petrarch. One day he[Pg xxvii] asked her physician how she was, and was told by him that her condition was very dangerous: on that occasion he composed the following sonnet:[E]—

This lovely spirit, if ordain'd to leave Its mortal tenement before its time, Heaven's fairest habitation shall receive And welcome her to breathe its sweetest clime. If she establish her abode between Mars and the planet-star of Beauty's queen, The sun will be obscured, so dense a cloud Of spirits from adjacent stars will crowd To gaze upon her beauty infinite. Say that she fixes on a lower sphere, Beneath the glorious sun, her beauty soon Will dim the splendour of inferior stars— Of Mars, of Venus, Mercury, and the Moon. She'll choose not Mars, but higher place than Mars; She will eclipse all planetary light, And Jupiter himself will seem less bright.

I trust that I have enough to say in favour of Petrarch to satisfy his rational admirers; but I quote this sonnet as an example of the worst style of Petrarch's poetry. I make the English reader welcome to rate my power of translating it at the very lowest estimation. He cannot go much further down than myself in the scale of valuation, especially if he has Italian enough to know that the exquisite mechanical harmony of Petrarch's style is beyond my reach. It has been alleged that this sonnet shows how much the mind of Petrarch had been influenced by his Platonic studies; but if Plato had written poetry he would never have been so extravagant.

Petrarch, on his return from Germany, had found the old Pope, John XXII., intent on two speculations, to both of which he lent his enthusiastic aid. One of them was a futile attempt to renew the crusades, from which Europe had reposed for a hundred years. The other was the transfer of the holy seat to Rome. The execution of this plan, for which Petrarch sighed as if it were to bring about the millennium, and which was not accomplished by another Pope without embroiling him with his Cardinals, was nevertheless more practicable than capturing Jerusalem. We are told by several Italian writers that the aged Pontiff, moved by repeated entreaties from the Romans, as well as by the remorse of his conscience, thought seriously of effecting this restoration; but the sincerity of his intentions is made questionable by the fact that he never fixed himself at Rome. He wrote, it is true, to Rome in 1333, ordering his palaces and gardens to be repaired; but the troubles which continued to agitate the city were alleged by him as too alarming for his safety there, and he repaired to Bologna to wait for quieter times.

On both of the above subjects, namely, the insane crusades and the more feasible restoration of the papal court to Rome, Petrarch[Pg xxviii] wrote with devoted zeal; they are both alluded to in his twenty-second sonnet.

The death of John XXII. left the Cardinals divided into two great factions. The first was that of the French, at the head of which stood Cardinal Taillerand, son of the beautiful Brunissende de Foix, whose charms were supposed to have detained Pope Clement V. in France. The Italian Cardinals, who formed the opposite faction, had for their chief the Cardinal Colonna. The French party, being the more numerous, were, in some sort, masters of the election; they offered the tiara to Cardinal de Commenges, on condition that he would promise not to transfer the papal court to Rome. That prelate showed himself worthy of the dignity, by refusing to accept it on such terms.

To the surprise of the world, the choice of the conclave fell at last on James Founder, said to be the son of a baker at Savordun, who had been bred as a monk of Citeaux, and always wore the dress of the order. Hence he was called the White Cardinal. He was wholly unlike his portly predecessor John in figure and address, being small in stature, pale in complexion, and weak in voice. He expressed his own astonishment at the honour conferred on him, saying that they had elected an ass. If we may believe Petrarch, he did himself no injustice in likening himself to that quadruped; but our poet was somewhat harsh in his judgment of this Pontiff. He took the name of Benedict XII.

Shortly after his exaltation, Benedict received ambassadors from Rome, earnestly imploring him to bring back the sacred seat to their city; and Petrarch thought he could not serve the embassy better than by publishing a poem in Latin verse, exhibiting Rome in the character of a desolate matron imploring her husband to return to her. Benedict applauded the author of the epistle, but declined complying with its prayer. Instead of revisiting Italy, his Holiness ordered a magnificent and costly palace to be constructed for him at Avignon. Hitherto, it would seem that the Popes had lived in hired houses. In imitation of their Pontiff, the Cardinals set about building superb mansions, to the unbounded indignation of Petrarch, who saw in these new habitations not only a graceless and unchristian spirit of luxury, but a sure indication that their owners had no thoughts of removing to Rome.

In the January of the following year, Pope Benedict presented our poet with the canonicate of Lombes, with the expectancy of the first prebend which should become vacant. This preferment Petrarch is supposed to have owed to the influence of Cardinal Colonna.

The troubles which at this time agitated Italy drew to Avignon, in the year 1335, a personage who holds a pre-eminent interest in the life of Petrarch, namely, Azzo da Correggio, who was sent thither by the Scaligeri of Parma. The State of Parma had be[Pg xxix]longed originally to the popes; but two powerful families, the Rossis and the Correggios, had profited by the quarrels between the church and the empire to usurp the government, and during five-and-twenty years, Gilberto Correggio and Rolando Rossi alternately lost and won the sovereignty, till, at last, the confederate princes took the city, and conferred the government of it on Guido Correggio, the greatest enemy of the Rossis.

Gilbert Correggio left at his death a widow, the sister of Cane de la Scala, and four sons, Guido, Simone, Azzo, and Giovanni. It is only with Azzo that we are particularly concerned in the history of Petrarch.

Azzo was born in the year 1303, being thus a year older than our poet. Originally intended for the church, he preferred the sword to the crozier, and became a distinguished soldier. He married the daughter of Luigi Gonzagua, lord of Mantua. He was a man of bold original spirit, and so indefatigable that he acquired the name of Iron-foot. Nor was his energy merely physical; he read much, and forgot nothing—his memory was a library. Azzo's character, to be sure, even with allowance for turbulent times, is not invulnerable at all points to a rigid scrutiny; and, notwithstanding all the praises of Petrarch, who dedicated to him his Treatise on a Solitary Life in 1366, his political career contained some acts of perfidy. But we must inure ourselves, in the biography of Petrarch, to his over-estimation of favourites in the article of morals.

It was not long ere Petrarch was called upon to give a substantial proof of his regard for Azzo. After the seizure of Parma by the confederate princes, Marsilio di Rossi, brother of Rolando, went to Paris to demand assistance from the French king. The King of Bohemia had given over the government of Parma to him and his brothers, and the Rossi now saw it with grief assigned to his enemies, the Correggios. Marsilio could obtain no succour from the French, who were now busy in preparing for war with the English; so he carried to the Pope at Avignon his complaints against the alleged injustice of the lords of Verona and the Correggios in breaking an express treaty which they had made with the house of Rossi.

Azzo had the threefold task of defending, before the Pope's tribunal, the lords of Verona, whose envoy he was; the rights of his family, which were attacked; and his own personal character, which was charged with some grave objections. Revering the eloquence and influence of Petrarch, he importuned him to be his public defender. Our poet, as we have seen, had studied the law, but had never followed the profession. "It is not my vocation," he says, in his preface to his Familiar Epistles, "to undertake the defence of others. I detest the bar; I love retirement; I despise money; and, if I tried to let out my tongue for hire, my nature would revolt at the attempt."[Pg xxx]

But what Petrarch would not undertake either from taste or motives of interest, he undertook at the call of friendship. He pleaded the cause of Azzo before the Pope and Cardinals; it was a finely-interesting cause, that afforded a vast field for his eloquence. He brought off his client triumphantly; and the Rossis were defeated in their demand.

At the same time, it is a proud trait in Petrarch's character that he showed himself on this occasion not only an orator and a lawyer, but a perfect gentleman. In the midst of all his zealous pleading, he stooped neither to satire nor personality against the opposing party. He could say, with all the boldness of truth, in a letter to Ugolino di Rossi, the Bishop of Parma, "I pleaded against your house for Azzo Correggio, but you were present at the pleading; do me justice, and confess that I carefully avoided not only attacks on your family and reputation, but even those railleries in which advocates so much delight."

On this occasion, Azzo had brought to Avignon, as his colleague in the lawsuit, Guglielmo da Pastrengo, who exercised the office of judge and notary at Verona. He was a man of deep knowledge in the law; versed, besides, in every branch of elegant learning, he was a poet into the bargain. In Petrarch's many books of epistles, there are few letters addressed by him to this personage; but it is certain that they contracted a friendship at this period which endured for life.

All this time the Bishop of Lombes still continued at Rome; and, from time to time, solicited his friend Petrarch to join him. "Petrarch would have gladly joined him," says De Sade; "but he was detained at Avignon by his attachment to John Colonna and his love of Laura:" a whimsical junction of detaining causes, in which the fascination of the Cardinal may easily be supposed to have been weaker than that of Laura. In writing to our poet, at Avignon, the Bishop rallied Petrarch on the imaginary existence of the object of his passion. Some stupid readers of the Bishop's letter, in subsequent times, took it into their heads that there was a literal proof in the prelate's jesting epistle of our poet's passion for Laura being a phantom and a fiction. But, possible as it may be, that the Bishop in reality suspected him to exaggerate the flame of his devotion for the two great objects of his idolatry, Laura and St. Augustine, he writes in a vein of pleasantry that need not be taken for grave accusation. "You are befooling us all, my dear Petrarch," says the prelate; "and it is wonderful that at so tender an age (Petrarch's tender age was at this time thirty-one) you can deceive the world with so much art and success. And, not content with deceiving the world, you would fain deceive Heaven itself. You make a semblance of loving St. Augustine and his works; but, in your heart, you love the poets and the philosophers. Your Laura is a phantom created by your imagination for the exercise of your poetry. Your verse, your[Pg xxxi] love, your sighs, are all a fiction; or, if there is anything real in your passion, it is not for the lady Laura, but for the laurel—that is, the crown of poets. I have been your dupe for some time, and, whilst you showed a strong desire to visit Rome, I hoped to welcome you there. But my eyes are now opened to all your rogueries, which nevertheless, will not prevent me from loving you."

Petrarch, in his answer to the Bishop,[F] says, "My father, if I love the poets, I only follow, in this respect, the example of St. Augustine. I take the sainted father himself to witness the sincerity of my attachment to him. He is now in a place where he can neither deceive nor be deceived. I flatter myself that he pities my errors, especially when he recalls his own." St. Augustine had been somewhat profligate in his younger days.

"As to Laura," continues the poet, "would to Heaven that she were only an imaginary personage, and my passion for her only a pastime! Alas! it is a madness which it would be difficult and painful to feign for any length of time; and what an extravagance it would be to affect such a passion! One may counterfeit illness by action, by voice, and by manner, but no one in health can give himself the true air and complexion of disease. How often have you yourself been witness of my paleness and my sufferings! I know very well that you speak only in irony: it is your favourite figure of speech, but I hope that time will cicatrize these wounds of my spirit, and that Augustine, whom I pretend to love, will furnish me with a defence against a Laura who does not exist."

Years had now elapsed since Petrarch had conceived his passion for Laura; and it was obviously doomed to be a source of hopeless torment to him as long as he should continue near her; for she could breathe no more encouragement on his love than what was barely sufficient to keep it alive; and, if she had bestowed more favour on him, the consequences might have been ultimately most tragic to both of them. His own reflections, and the advice of his friends, suggested that absence and change of objects were the only means likely to lessen his misery; he determined, therefore, to travel once more, and set out for Rome in 1335.

The wish to assuage his passion, by means of absence, was his principal motive for going again upon his travels; but, before he could wind up his resolution to depart, the state of his mind bordered on distraction. One day he observed a country girl washing the veil of Laura; a sudden trembling seized him—and, though the heat of the weather was intense, he grew cold and shivered. For some time he was incapable of applying to study or business. His soul, he said, was like a field of battle, where his passion and reason held continual conflict. In his calmer moments, many agreeable motives for travelling suggested them[Pg xxxii]selves to his mind. He had a strong desire to visit Rome, where he was sure of finding the kindest welcome from the Bishop of Lombes. He was to pass through Paris also; and there he had left some valued friends, to whom he had promised that he would return. At the head of those friends were Dionisio dal Borgo San Sepolcro and Roberto Bardi, a Florentine, whom the Pope had lately made chancellor of the Church of Paris, and given him the canonship of Nôtre Dame. Dionisio dal Borgo was a native of Tuscany, and one of the Roberti family. His name in literature was so considerable that Filippo Villani thought it worth while to write his life. Petrarch wrote his funeral eulogy, and alludes to Dionisio's power of reading futurity by the stars. But Petrarch had not a grain of faith in astrology; on the contrary, he has himself recorded that he derided it. After having obtained, with some difficulty, the permission of Cardinal Colonna, he took leave of his friends at Avignon, and set out for Marseilles. Embarking there in a ship that was setting sail for Civita Vecchia, he concealed his name, and gave himself out for a pilgrim going to worship at Rome. Great was his joy when, from the deck, he could discover the coast of his beloved Italy. It was a joy, nevertheless, chastened by one indomitable recollection—that of the idol he had left behind. On his landing he perceived a laurel tree; its name seemed to typify her who dwelt for ever in his heart: he flew to embrace it; but in his transports overlooked a brook that was between them, into which he fell—and the accident caused him to swoon. Always occupied with Laura, he says, "On those shores washed by the Tyrrhene sea, I beheld that stately laurel which always warms my imagination, and, through my impatience, fell breathless into the intervening stream. I was alone, and in the woods, yet I blushed at my own heedlessness; for, to the reflecting mind, no witness is necessary to excite the emotion of shame."

It was not easy for Petrarch to pass from the coast of Tuscany to Rome; for war between the Ursini and Colonna houses had been renewed with more fury than ever, and filled all the surrounding country with armed men. As he had no escort, he took refuge in the castle of Capranica, where he was hospitably received by Orso, Count of Anguillara, who had married Agnes Colonna, sister of the Cardinal and the Bishop. In his letter to the latter, Petrarch luxuriates in describing the romantic and rich landscape of Capranica, a country believed by the ancients to have been the first that was cultivated under the reign of Saturn. He draws, however, a frightful contrast to its rural picture in the horrors of war which here prevailed. "Peace," he says, "is the only charm which I could not find in this beautiful region. The shepherd, instead of guarding against wolves, goes armed into the woods to defend himself against men. The labourer, in a coat of mail, uses a lance instead of a goad, to drive his cattle.[Pg xxxiii] The fowler covers himself with a shield as he draws his nets; the fisherman carries a sword whilst he hooks his fish; and the native draws water from the well in an old rusty casque, instead of a pail. In a word, arms are used here as tools and implements for all the labours of the field, and all the wants of men. In the night are heard dreadful howlings round the walls of towns, and and in the day terrible voices crying incessantly to arms. What music is this compared with those soft and harmonious sounds which. I drew from my lute at Avignon!"

On his arrival at Capranica, Petrarch despatched a courier to the Bishop of Lombes, informing him where he was, and of his inability to get to Rome, all roads to it being beset by the enemy. The Bishop expressed great joy at his friend's arrival in Italy, and went to meet him at Capranica, with Stefano Colonna, his brother, senator of Rome. They had with them only a troop of one hundred horsemen; and, considering that the enemy kept possession of the country with five hundred men, it is wonderful that they met with no difficulties on their route; but the reputation of the Colonnas had struck terror into the hostile camp. They entered Rome without having had a single skirmish with the enemy. Stefano Colonna, in his quality of senator, occupied the Capitol, where he assigned apartments to Petrarch; and the poet was lodged on that famous hill which Scipio, Metellus, and Pompey, had ascended in triumph. Petrarch was received and treated by the Colonnas Like a child of their family. The venerable old Stefano, who had known him at Avignon, loaded our poet with kindness. But, of all the family, it would seem that Petrarch delighted most in the conversation of Giovanni da S. Vito, a younger brother of the aged Stefano, and uncle of the Cardinal and Bishop. Their tastes were congenial. Giovanni had made a particular study of the antiquities of Rome; he was, therefore, a most welcome cicerone to our poet, being, perhaps, the only Roman then alive, who understood the subject deeply, if we except Cola di Rienzo, of whom we shall soon have occasion to speak.

In company with Giovanni, Petrarch inspected the relics of the "eternal city:" the former was more versed than his companion in ancient history, but the other surpassed him in acquaintance with modern times, as well as with the objects of antiquity that stood immediately before them.

What an interesting object is Petrarch contemplating the ruins of Rome! He wrote to the Cardinal Colonna as follows:—"I gave you so long an account of Capranica that you may naturally expect a still longer description of Rome. My materials for this subject are, indeed, inexhaustible; but they will serve for some future opportunity. At present, I am so wonder-struck by so many great objects that I know not where to begin. One circumstance, however, I cannot omit, which has turned out contrary to[Pg xxxiv] your surmises. You represented to me that Rome was a city in ruins, and that it would not come up to the imagination I had formed of it; but this has not happened—on the contrary, my most sanguine expectations have been surpassed. Rome is greater, and her remains are more awful, than my imagination had conceived. It is not matter of wonder that she acquired universal dominion. I am only surprised that it was so late before she came to it."

In the midst of his meditations among the relics of Rome, Petrarch was struck by the ignorance about their forefathers, with which the natives looked on those monuments. The veneration which they had for them was vague and uninformed. "It is lamentable," he says, "that nowhere in the world is Rome less known than at Rome."

It is not exactly known in what month Petrarch left the Roman capital; but, between his departure from that city, and his return to the banks of the Rhone, he took an extensive tour over Europe. He made a voyage along its southern coasts, passed the straits of Gibraltar, and sailed as far northward as the British shores. During his wanderings, he wrote a letter to Tommaso da Messina, containing a long geographical dissertation on the island of Thule.

Petrarch approached the British shores; why were they not fated to have the honour of receiving him? Ah! but who was there, then, in England that was capable of receiving him? Chaucer was but a child. We had the names of some learned men, but our language had no literature. Time works wonders in a few centuries; and England, now proud of her Shakespeare and her Verulam, looks not with envy on the glory of any earthly nation. During his excitement by these travels, a singular change took place in our poet's habitual feelings. He recovered his health and spirits; he could bear to think of Laura with equanimity, and his countenance resumed the cheerfulness that was natural to a man in the strength of his age. Nay, he became so sanguine in his belief that he had overcome his passion as to jest at his past sufferings; and, in this gay state of mind, he came back to Avignon. This was the crowning misfortune of his life. He saw Laura once more; he was enthralled anew; and he might now laugh in agony at his late self-congratulations on his delivery from her enchantment. With all the pity that we bestow on unfortunate love, and with all the respect that we owe to its constancy, still we cannot look but with a regret amounting to impatience on a man returning to the spot that was to rekindle his passion as recklessly as a moth to the candle, and binding himself over for life to an affection that was worse than hopeless, inasmuch as its success would bring more misery than its failure. It is said that Petrarch, if it had not been for this passion, would not have been the poet that he was. Not, perhaps, so good an amatory poet; but I firmly believe that he would have been a more various[Pg xxxv] and masculine, and, upon the whole, a greater poet, if he had never been bewitched by Laura. However, he did return to take possession of his canonicate at Lombes, and to lose possession of his peace of mind.

In the April of the following year, 1336, he made an excursion, in company with his brother Gherardo, to the top of Mount Ventoux, in the neighbourhood of Avignon; a full description of which he sent in a letter to Dionisio dal Borgo a San Sepolcro; but there is nothing peculiarly interesting in this occurrence.

A more important event in his life took place during the following year, 1337—namely, that he had a son born to him, whom he christened by the name of John, and to whom he acknowledged his relationship of paternity. With all his philosophy and platonic raptures about Laura, Petrarch was still subject to the passions of ordinary men, and had a mistress at Avignon who was kinder to him than Laura. Her name and history have been consigned to inscrutable obscurity: the same woman afterwards bore him a daughter, whose name was Francesca, and who proved a great solace to him in his old age. His biographers extol the magnanimity of Laura for displaying no anger at our poet for what they choose to call this discovery of his infidelity to her; but, as we have no reason to suppose that Laura ever bestowed one favour on Petrarch beyond a pleasant look, it is difficult to perceive her right to command his unspotted faith. At all events, she would have done no good to her own reputation if she had stormed at the lapse of her lover's virtue.

In a small city like Avignon, the scandal of his intrigue would naturally be a matter of regret to his friends and of triumph to his enemies. Petrarch felt his situation, and, unable to calm his mind either by the advice of his friend Dionisio dal Borgo, or by the perusal of his favourite author, St. Augustine, he resolved to seek a rural retreat, where he might at least hide his tears and his mortification. Unhappily he chose a spot not far enough from Laura—namely, Vaucluse, which is fifteen Italian, or about fourteen English, miles from Avignon.

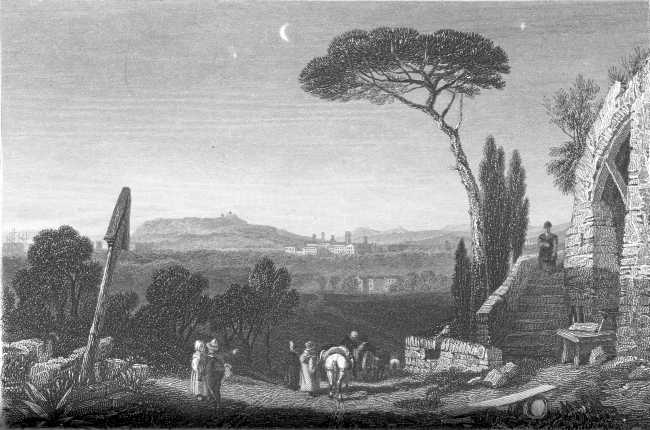

Vaucluse, or Vallis Clausa, the shut-up valley, is a most beautiful spot, watered by the windings of the Sorgue. Along the river there are on one side most verdant plains and meadows, here and there shadowed by trees. On the other side are hills covered with corn and vineyards. Where the Sorgue rises, the view terminates in the cloud-capt ridges of the mountains Luberoux and Ventoux. This was the place which Petrarch had visited with such delight when he was a schoolboy, and at the sight of which he exclaimed "that he would prefer it as a residence to the most splendid city."

It is, indeed, one of the loveliest seclusions in the world. It terminates in a semicircle of rocks of stupendous height, that seem to have been hewn down perpendicularly. At the head and[Pg xxxvi] centre of the vast amphitheatre, and at the foot of one of its enormous rocks, there is a cavern of proportional size, hollowed out by the hand of nature. Its opening is an arch sixty feet high; but it is a double cavern, there being an interior one with an entrance thirty feet high. In the midst of these there is an oval basin, having eighteen fathoms for its longest diameter, and from this basin rises the copious stream which forms the Sorgue. The surface of the fountain is black, an appearance produced by its depth, from the darkness of the rocks, and the obscurity of the cavern; for, on being brought to light, nothing can be clearer than its water. Though beautiful to the eye, it is harsh to the taste, but is excellent for tanning and dyeing; and it is said to promote the growth of a plant which fattens oxen and is good for hens during incubation. Strabo and Pliny the naturalist both speak of its possessing this property.

The river Sorgue, which issues from this cavern, divides in its progress into various branches; it waters many parts of Provence, receives several tributary streams, and, after reuniting its branches, falls into the Rhone near Avignon.

Resolving to fix his residence here, Petrarch bought a little cottage and an adjoining field, and repaired to Vaucluse with no other companions than his books. To this day the ruins of a small house are shown at Vaucluse, which tradition says was his habitation.

If his object was to forget Laura, the composition of sonnets upon her in this hermitage was unlikely to be an antidote to his recollections. It would seem as if he meant to cherish rather than to get rid of his love. But, if he nursed his passion, it was a dry-nursing; for he led a lonely, ascetic, and, if it were not for his studies, we might say a savage life. In one of his letters, written not long after his settling at Vaucluse, he says, "Here I make war upon my senses, and treat them as my enemies. My eyes, which have drawn me into a thousand difficulties, see no longer either gold, or precious stones, or ivory, or purple; they behold nothing save the water, the firmament, and the rocks. The only female who comes within their sight is a swarthy old woman, dry and parched as the Lybian deserts. My ears are no longer courted by those harmonious instruments and voices which have so often transported my soul: they hear nothing but the lowing of cattle, the bleating of sheep, the warbling of birds, and the murmurs of the river.